History of Printing in the World and Iran

The art of printing, in fact, dates back centuries before Gutenberg whose name is recorded in history as the inventor of printing. The Assyrians, several millennia before Christ, used to stamp clay tablets with engraved seals. The use of movable type began between the years 1051 and 1058 in China. The inventor of these types was a man named Bi Sheng, who made them out of clay. Although later attempts with hand-carved and tin types were unsuccessful, wooden movable types became popular. In 1440, Gutenberg apparently unaware of the Chinese method invented his own movable type system, designing a separate cast for each letter of the alphabet. While the Chinese had first created movable type, Gutenberg, who was a goldsmith by trade, developed an alloy of lead and antimony that produced durable type neither too hard nor too soft. He also formulated a suitable printing ink, and by overcoming these technical challenges, succeeded in creating a fully functional printing process.

About twenty years after Gutenberg’s first experiments with printing, this new craft using raised surfaces for impression spread modestly in cities such as Venice, Florence, Paris, and Lyon. However, Gutenberg’s press, due to its high production cost, was accessible only to the wealthy, and for a long time it did not gain widespread popularity. Nearly three centuries later, in 1796, a German playwright named Alois Senefelder invented lithography or stone printing. Each limestone block engraved with text or images could yield around 750 quality impressions before wearing out. Although different accounts exist regarding the beginning of lithographic printing in Iran, it is widely believed that Mirza Saleh Shirazi was the first to introduce it. Having been sent to Europe by the Iranian government to study modern sciences and arts, he returned with a lithographic press and established it in Tabriz in 1250 AH (approximately 1834 AD).

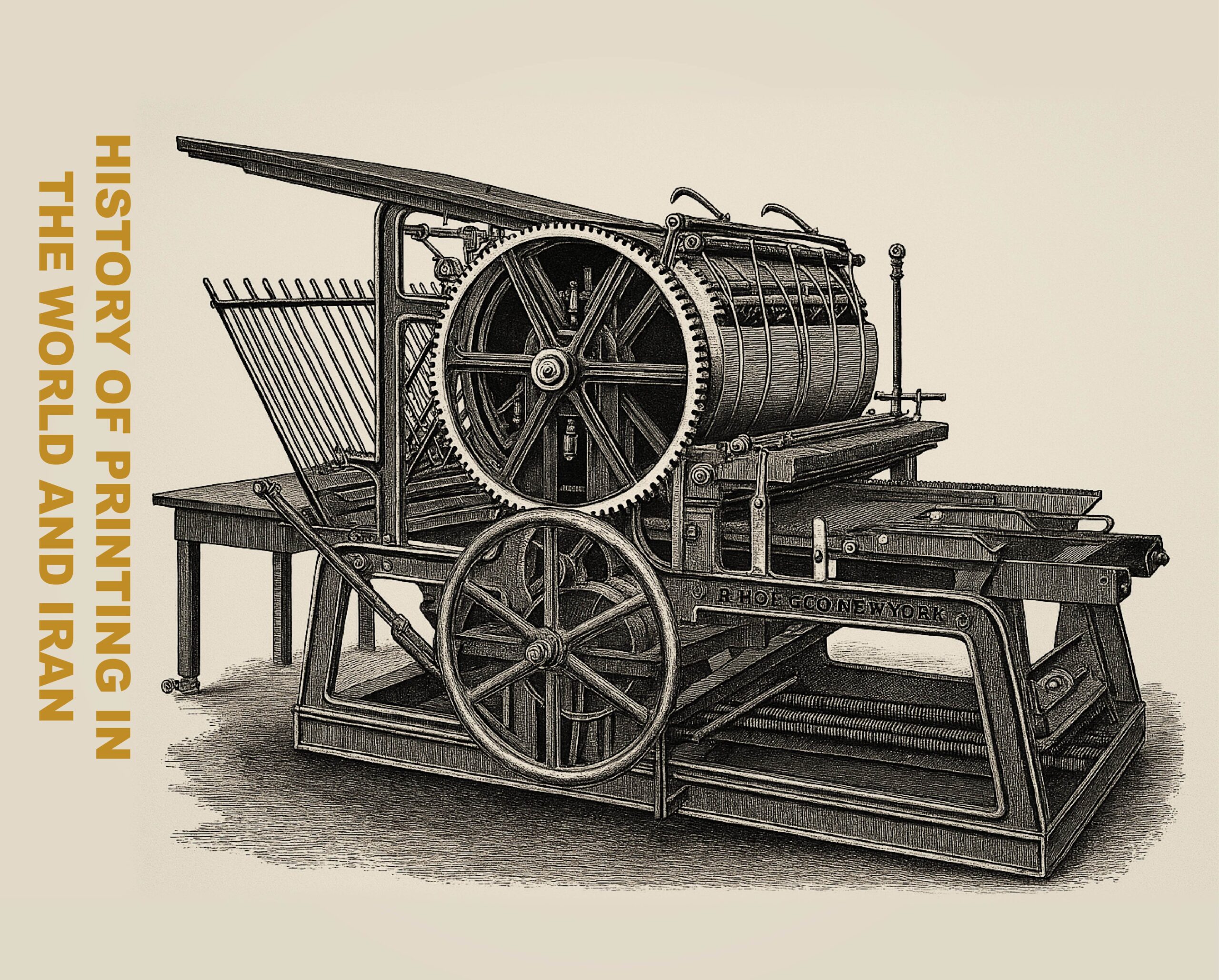

The lithographic printing house in Tabriz soon inspired similar establishments in Tehran, Isfahan, and later in other major cities across Iran. For more than fifty years, lithography remained the dominant printing method in the country, and up until the late Qajar period, nearly all printed materials in Iran were produced by this technique. Interestingly, eight years before the arrival of lithography, movable type printing using lead letters had already been introduced, but due to its higher cost and complexity, it was quickly abandoned in favor of lithography. It was only toward the end of the Qajar era that lead typesetting was revived and regained popularity. The process was relatively simple: sheets of paper were pressed against inked, raised lead type blocks, transferring the letters onto the page. Early newspaper typesetting was done manually, but later this work was automated with typesetting machines most notably the Linotype, invented in 1886 which significantly increased printing speed and efficiency. As technology advanced, mechanical typesetting gradually gave way to electronic systems.

Some scholars trace the origins of printing in Iran back to the Ilkhanid period, while others suggest that Persian-speaking Jewish communities were among the first to recognize the importance of printed books.

In 1639, three books in Persian language and script were printed in Leiden, the Netherlands, by Christian missionary societies to promote Christianity. This printing house is considered the first to produce Persian-language books in the world. According to historical evidence, the first book ever printed inside Iran was the Psalms of David (Zabur-e Davood), printed in 1638 in New Julfa, Isfahan, in Armenian script by Armenian priests. The Armenians were the first ethnic group in Iran to establish their own printing press and publish religious texts freely. They ranked fifteenth among all nations in the world in terms of the historical timeline of printing a remarkable achievement made possible by the tolerant and supportive environment fostered by Shah Abbas I and other Safavid rulers. About thirty years after their relocation to New Julfa, the Armenians set up a printing workshop and began publishing books.

Travelers’ accounts particularly those of Jean Chardin indicate that during the Safavid era, many Iranians were already aware of printing technology and eager to introduce it to their homeland. Later, during the Afsharid period under Nader Shah, travelers such as John Pinkerton and Jonas Hanway mentioned pamphlets printed in Latin and Arabic being circulated in Iran. A major transformation in printing and publishing including books, newspapers, and other printed materials occurred during the governorship of Abbas Mirza Qajar, following the Russo-Persian wars. Historical records show that in 1233 AH (1818 AD), Agha Zeyn al-Abedin Tabrizi, with the support of Abbas Mirza, established the first confirmed printing house in Tabriz. The Fathnameh, written by Mirza Abolqasem Qaem Maqam Farahani as a detailed account of the Iran–Russia wars, is considered the first Persian book printed in Iran, published in 1234 AH (1819 AD).

An examination of the earliest printed books reveals that the government at the time used printing primarily for its own political and educational objectives. Most publications were historical, religious, or literary in nature, or aimed at promoting public health, civic awareness, and modern social values. Around 1240 AH (1824 AD), roughly seven years after the establishment of the Tabriz press, Mirza Zeyn al-Abedin was summoned to Tehran by Fath Ali Shah Qajar to found a new state printing house. Lithographic printing, interestingly, became popular in Iran after lead-type printing. Jafar Khan Tabrizi was sent to Moscow to learn the technique, and upon his return in 1239–1240 AH (1823–1824 AD), he brought a lithographic press to Tabriz.

The first lithographic book printed in Iran was a Qur’an, published in 1248 AH (1832 AD) by Mirza Asadollah in Tabriz. Three years later, he printed Zad al-Ma’ad (a religious text) using the same method. Lithographic printing soon spread beyond Tabriz and Tehran to many other Iranian cities. By the reign of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, lead-type printing once again gained prominence after more than half a century.

Lithography even influenced the aesthetics of Persian calligraphy, introducing changes to handwriting styles due to technical constraints of stone printing. The establishment of the Dar ul-Fonoon School (Iran’s first modern educational institution) had a significant impact on the development of printing. The need for textbooks and instructional materials led to the creation of a dedicated workshop within the school for publishing academic works, teaching resources, and other educational books. This small printing unit, known as Dar al-Taba’eh Khasseh Elmiyeh Mobarakeh Dar ul-Fonoon Tehran, was founded around 1268 AH (1851 AD) under the supervision of Aliqoli Mirza Etezad al-Saltaneh and operated until about 1300 AH (1883 AD), producing nearly forty educational titles. A state printing house, under various names, was also established during Naser al-Din Shah’s reign for printing books and newspapers.

The Constitutional Revolution in the early 20th century played a decisive role in expanding the printing industry in Iran. The number of newspapers and their circulation grew rapidly, and public interest in political and social writings increased. The need to distribute political pamphlets, manifestos, and underground publications led to the emergence of gelatin printing, which was later replaced by stencil duplication. Small secret printing presses were reportedly used for such purposes. Shortly after the establishment of the First National Assembly (Majles-e Shora-ye Melli), the Parliament Printing House was founded to print its official journal and documents. It soon became the largest and most advanced press in the country. Another major facility, the Imperial Printing House, was later established under Abdollah Khan Qajar, a prominent figure in Iran’s printing industry, and remained active until 1328 AH (1910 AD).

During the reign of Mohammad Ali Mirza Qajar, private lead-type printing houses gradually replaced state-owned lithographic presses. By around 1330 AH (1912 AD), only a few lithographic presses were still in operation. Between 1307 and 1317 SH (1928–1938 AD), the government initiated new efforts to modernize textbook printing across the country. The founding of Tehran University and other new educational institutions, along with the expansion of the state and military, created an urgent need for large-scale printing operations. This led to the establishment of several major government presses, including those of the Army, Bank Melli Iran, Iran Tobacco Company, and Railway Organization, all designed to meet the state’s internal printing demands independently.

From 1941 to 1953, despite intermittent censorship and government interference, the printing and publishing industry in Iran experienced a period of relative freedom and expansion. The number of periodicals increased significantly after the fall of Reza Shah. During this time, Taban Printing House, the first private press equipped with modern automatic machines, marked a major milestone in Iran’s printing modernization. The Bank Melli Printing House also adopted new rotary presses, while the Ettelaat Press, already one of the largest in the country before 1941, expanded and upgraded its facilities.

In the 1950s, new rotary offset presses and two- and four-color printing machines were imported to Iran, ushering in a new era of technological advancement in the printing sector. Prominent presses of that decade included Keyhan and Sepehr, both pioneers in offset printing. During the 1960s, the industry entered another stage of growth, driven by the introduction of modern educational textbooks, inexpensive pocket-sized books, and specialized training in printing technology. Until the mid-1960s, printing education in Iran was mostly apprenticeship-based, passed from master to apprentice within workshops. In 1965, a technical printing department was officially established at a vocational high school level, and from 1966 onward, several Iranian students were sent to Austria to study modern printing techniques.

During the 1979 Islamic Revolution, printing houses became some of the most critical and active centers of opposition against the Pahlavi regime. Between the departure of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in January 1979 and the beginning of the Iran–Iraq War in September 1980, more than 350 newspapers were published in Iran.

Since the Revolution, the Iranian printing industry has grown remarkably due to several key factors: the increase in book and magazine titles; the easing of censorship (except during brief periods); the expansion of printing education; the launch of specialized trade journals such as San’at-e Chap (“Printing Industry”) and Chap va Bastebandi (“Printing & Packaging”); and the strengthening of professional printing associations. The introduction of computers and digital networks revolutionized the industry, transforming information and communication worldwide. The growth of universities, rising literacy rates, and an expanding young population further fueled demand for printed materials.

In 1992 (1371 SH), color printing was first introduced in Iranian newspapers, with Hamshahri becoming the country’s first full-color daily. That same year, a new regulation was passed regarding the establishment and supervision of printing houses and related units. Today, several specialized and semi-specialized publications cover the printing field, including The Printing Industry Monthly, Print & Packaging Monthly, and Printing & Publishing Monthly. Government presses continue to handle the printing of stamps, securities, bus tickets, and other official documents under strict regulations. A specialized Banknote Printing House was established in 1982 and began full operations the following year. Since 1988, all Iranian currency has been printed domestically. In recognition of the industry’s importance, the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution designated September 2 (11 Shahrivar) as National Printing Industry Day in Iran.